Six decades ago I arrived at the port of Talara on the edge of the northern desert after a three-week trans-Atlantic, trans Panama voyage on a small oil tanker, El Lobo out of Cardiff. I had boarded as a supernumerary member of the crew the day after being released from university. For a night or two I was a guest nearby of the Lobitos Oil Co at one of their spacious bungalows in the desert, surrounded by clanking well pumps, I was attended by mayordomos in white gloves, something unheard of in England, my England, of the grey post-war ’40s and ’50s.

A week or two later at a general store in Ayabaca, a market town in the forgotten depths of the Peruvian Sierra near the Ecuador frontier, I treated myself after a jolting night on the back of a lorry to a bottle of beer.

In those days beer was sold in macho pint bottles. The store did not have a bottle opener. A quiet middle-aged resident was propping up the wood counter. He said, “Gringito,” signaling me to bring him the bottle. He smiled, put the top in his mouth. Without effort, he bit off the cap. Foam flowed. He spat out the bottle top into the floor sawdust.

I had not heard in my 21 years of this solution to a problem I had not imagined existed. I did not know if it was permitted, even physically possible. I have since seen it done from time to time, say on a wooden barge on the Ucayali or on a distant Andean patio.

Like any South American, I would learn to pop a bottle with the back of a table knife, a machete, or the fender of someone else’s Toyota. On this occasion, in any case, biting off the cap gave me a shock which has remained as you see with me for more than half a century. An education in no-nonsense courtesy. Until then I had been cossetted by English rules. The proper way of doing things is the only way.

Fear God, Honour The King

I see, looking back, a new un-English life of spontaneous friendliness, opening new opportunities beyond stiff self-satisfaction. Our school motto among the Greco-Roman porticos was Fear God, Honour The King. Not much wiggle room there.

With the jaw-clench bottle top eye opener, I began to leave behind some of the certainties of being English. I was edging into a world beyond gentle-fingered Wimple St dentists, rinsed glasses. Places with names like Lydeard St Lawrence, West Bagborough, Trumpington Street.

I signaled my new compañero to have a swig. We would have taken it in turns, a first for me, to reach the bottom of the bottle. My Latin was better than our combined Spanish. The job was done with a matey Salud as the last man emptied the dregs into the sawdust.

In those days sons used to write weekly letters home to Mum. I did not recount this bottle-cap incident. Mum, a doctor, might have panicked, sent a return ticket on the PSNC, Pacific Steam Navigation Co mailboat. My soft wartime English haw-haw teeth would never cope with even today’s sissy half-pint throwaways. I still take my occasional hit from the bottle, even in a restaurant, wiping the top with the palm of my hand remembering my maestro.

Do you ride?

On the Ayabaca plaza outside that same day, I ran into, as one did in those days, the Sub Prefect, a Limeño not much older than me. A job for the boy’s political appointee of the Manuel Prado government, he would tell me later.

“Do you ride?” I nodded. “Leave your bag in my office.” He was off for a few days to deal with this and that in the outback. We would be accompanied by an ADC, a friendly young local who had a revolver in a holster on his waist under his jacket.

This was the first person I had met who carried a gun. Life went up a new couple of notches. Another something not to tell Mum. I was taken off to buy a proper sombrero and, as I recall, a poncho to throw over the saddle and to keep me covered through the tropic night.

On horses supplied by each pueblo, we clattered through a movie set of dry jagged peaks up and down old paths, forded rocky rivers stopping to chat at haciendas and tiled adobe villages. One day we were joined by a group of landowners armed with revolvers and carbines in long holsters built into the front of their saddles. Sitting on our horses in a wide semi-circle in front of us stood a dozen men, gesturing angrily, talking loudly, campesinos armed as was everyone in those days with machetes.

The matter was, as often in the valleys of the Andes, about water. Cactus, scrawny cattle, mangy dogs, buzzards were the wildlife. I knew exactly where I was, who was who. The leader of the landowners, on his arrogantly well-fed horse with his henchmen was Lee Marvin. My friend the Sub Prefect was Clint Eastwood, the county sheriff. In the middle, protesting at the head of his hardscrabble neighbours was Jimmy Stewart, rising above himself.

Here I was with three of the legends of our time sitting on a scrawny pony in equatorial dust and heat. I was not in the mezzanine of the Leicester Square Odeon. A day or so later found us in Frias, a no-road pueblo.

How about a game of chess?

The scene was again the general store whose owner was a young Nissei. It was a meeting place with some chairs and tables. “Chess?” the owner said, “Chess?” I had been on the school team though I have never been able to plan more than a move ahead, much less spot what my opponent is plotting. I had just exited one of the world’s ancient universities, been schooled by some of the finest academic minds of the day.

We sat down. Within five minutes I had to knock over my King, acknowledging defeat in, what was it, seven, eight moves? It was not a defeat, it was a rout. He was in some Maestro class beyond my comprehension. Here I was in the back of tropical beyond. I had been slaughtered. A second game surrounded by a score of townsmen, some of them knowledgeable. Maybe I got to a dozen moves. With chess, there is no masquerade, nowhere to hide. I can remember the calm, good-humoured Japanese entirely pleasant face. I hope I had the grace to buy a few beers, a nothing price for what as you see, goes beyond a lesson.

As it had been with the bottle-opening, it was an education. I have over the years been knocked down a richly-deserved peg many times. In this case it was a painless privilege.

I have been living on the outskirts of Frias ever since, rarely learning lessons until it is yet again too late. I would love to have an annotated record of the games for my children, grandchildren to show them, unbelieving, how Grandad, just off the boat, had been mercilessly and oh so rightly samurai-ed.

A few days later returning to Ayabaca over new passes through different valleys, I took part in a horse race from which I was taught, though never properly absorbed, another lesson.

This was not a modest affair. I cannot remember how it was set up. The local folk lending us their horses to get us to the next valley decided to turn it into a sporting event. It would be a race, a two or three-hour run. Call it a score of miles uphill and down dale, fording rivers, running along cliffside paths. The locals knew the paths, the course.

We, us visitors, would choose our mounts. I knew well enough how to ride. I had not, however, the slightest talent, and still don’t, for judging a horse. As we milled around trying, in my case, to look as though I knew what I was about, an older man approached. “Gringito!” He took me to one of the ponies. “This is the one for you. It’s mine. You’re nice and light. I know you’ll look after her.”

I announced my horse. Long faces showed I had made the right choice. Of course, she might be Pegasus herself but if I had no idea of the route, the finish, it would be to little avail. I did the obvious, cantering behind a couple of well-mounted savvy locals.

The pace picked up. One of the two went up ahead, me tucked in a couple of lengths behind ready to make my break in the final furlong. Prudent yes, subtle no. The local pointed to a white house on the edge of the pueblo below, half a mile along our main path winding down the hill. A cry went up behind.

I looked back to see everyone turning down a side-path shortcut, the other smart rider streaking ahead. I jumped a ditch into a barren field and cut ahead of the main pack. The winner was, however, cantering with his sombrero waving, victorious, a disappointment to many. I had been odds-on favourite. I have forgotten what prize was won by the winner. It must have been worth the while because my Second place brought me a pair of battle-ready fighting cocks. These I gave to the owner of my pony.

You can draw your own lessons. They revolve around when to make your break and, how to spot where the smart money is really going.

This story I would certainly have sent to mum. Our family had been Londoners of the prosperous Forsyte genre. She would have enjoyed recounting it to her county sisters with the fighting cocks adding a macho touch of South America.

Returning home via the travelling circus

After three years in the Sierra and selva, I returned at the end of 1963 to London to work on Fleet Street. To get home I would cross the continent by land to Rio and catch the BOAC to spend Christmas with Mum. Puerto Maldonado was the Far East of Peru with no roads to Brazil or anywhere else. I pushed through the rubber plantations of Iberia and Inapari, walked and canoed across the Bolpebra tripartite frontier. I knew I was in Brazil when from a thatched house on stilts the radio was blaring a samba. They helped me hitch my hammock to their rafters.

I caught next morning a passing canoe on the Rio Acre to reach Brasiléia, a small dorp facing Cobija, a Bolivian outpost over the river. In the evening I went, like everyone, to the travelling circus. The lissome star of the show was Bolivian, 16, she told me. She was the trapeze artist. The cuerda floja was a good five feet above the ring. Everyone cheered and clapped. Soon the ringmaster, a jolly Brazilian pointed at me. “Hi Gringito! Come and show us what you can do!” More cheers.

The Bolivian girl came in her slight uniform and to applause, cheers pulled me into the ring. The ringmaster said quietly to me, just go along with it. He had a bucket of water which he signalled to the kids not to tell me about.

The Bolivian girl talked in a loud voice. “Nobody is going to do anything, are they children!” The ringmaster crept up behind. Kids shouted, “Look out behind you!” I turned slowly to give him time to keep behind me. Nothing to worry about! I gestured to the crowd. And so on. Finally the ringmaster, or maybe it was the girl herself, emptied the bucket over me. At the end of the show, the ringmaster sent the girl to bring me to him. “Hey, young sir! You did great! Excelente! Incredible talent! I want you to join my circus. We’re going on downriver. Get to Manaus for Christmas. All expenses paid.”

“He’s our new star!” he said to the girl, who nodded loyally, giving me a not very enthusiastic smile. The ringmaster looked at us both. He may even have said sotto voce, “She’s fallen for you.”

I thanked them and said I would consider it with the greatest interest. I still think of it 60 years on as the best job offer I have had.

The dark of the warm Amazon madrugada of 03:00 saw me on the riverbank with my hammock and kitbag. I caught the first canoe sliding swiftly silently downriver. It was two thousand miles by jungle and Mato Groso road to Rio. I caught the BOAC and was with Mum all present and correct at Pyleigh Manor Farm for Christmas.

I might not have learned much in these early outings into the heartland of South America. That said, when in the Amazon you find yourself in extreme peril do not think do not look back keep running till you are high, dry and home.

Things have since changed a little

My workplace these days is no longer a rowdy scrum of people, paper and phones. Today I sit in a glass-enclosed verandah which catches the afternoon sun, rendering it with its woodland and mountain views relentlessly restful. The family dog and cat breath gently from the polished hardwood planking. On the inside length is a 20-foot-high, two-foot-thick adobe wall on which hang family paintings, drawings, shelves of books, a 19th-century wind-up clock which tick-tocks and chimes through the day and Andean night.

The open side is glasshouse windowpanes looking onto a woodland of thick tall cedars, walnuts, Mexican Cherry, pisonays, and sub-tropical versions of plants like fuchsia, Kantu, deadly nightshade aka belladonna. Occasionally we see otters tree sloth and the Andean weasel. Toads and tree frogs, no snakes, few mosquitoes. Behind these to the North, rise snowcapped peaks and glaciers, the 6,000 m Cordillera Urubamba. On the other, a hundred yards away through the trees flows the Rio Vilcanota.

Fifty miles downstream the waters will plunge through the Machu Picchu gorge on their way into the still-distant Amazon. Flocks of parrots, hummingbirds, hawks and falcons, owls, migrators and river fowl, the garden varieties with names like Golden-billed Saltator, Black-backed Grosbeak, (yellow-black) Hooded Mountain-Tanager (tallow-blue) Chestnut-Hooded Siskin provide a video soundtrack from first light through sunset and on into the clear cold night of 2,950 m.

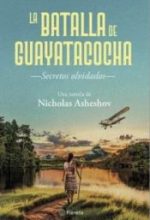

There I am sitting on a donut in a businesslike wooden chair. The laptop on the table erupts in a sleepy autoburp. I emerge from some daydream and write a few more paragraphs of ‘Forgotten Secrets’, my three-volume saga of a decades-long modern rebellion in the back country of the Amazon. The first book, published by Planeta, Madrid and Lima as La Batalla de Guayatacocha. Una novela de Nicholas Asheshov is in the bookshops.